The Link between Mass Shootings & Misogynistic Online Harassment

Mental Health, Technology-facilitated Gender-based Violence, Violence Against Women and Girls

11 July 2018

Media Contact

Years before he carried a shotgun into the Annapolis Capital Gazette, Jarrod Ramos set his sights on a former classmate, harassing and threatening her online until she feared for her safety. The United States accounts for the largest number of public mass shootings in the world, and 54 percent of these shootings are a biproduct of domestic violence. While many perpetrators of mass shootings have a history of violence against women, it’s also becoming increasingly clear that online gender-based violence (GBV), specifically, is a precursor to violence carried out offline.

With the rapid rise of social media and use of hand-held devices, violence experienced online and over mobile technology is an emerging public health and human rights concern that disproportionately affects women and girls, as well as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) individuals worldwide.

With the rapid rise of social media and use of hand-held devices, violence experienced online and over mobile technology is an emerging public health and human rights concern that disproportionately affects women and girls, as well as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) individuals worldwide.

‘Cyberbullying’, ‘online harassment’ and ‘cyberstalking’ have become increasingly prevalent in recent years. A study by the Pew Research Center found that 41 percent of adult Americans report experiencing harassment online, 18 percent of whom report having endured particularly severe forms of online harassment.

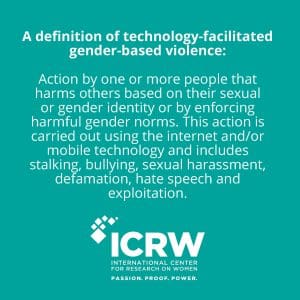

These behaviors, rooted in misogynistic and homophobic attitudes and enabled by technology, are all expressions of the same fundamental type of violence: technology-facilitated gender-based violence (GBV) – a term coined by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) to understand and capture the full range of motivations, tactics and impacts of these behaviors, as well as provide a foundation for measuring it.

These behaviors, rooted in misogynistic and homophobic attitudes and enabled by technology, are all expressions of the same fundamental type of violence: technology-facilitated gender-based violence (GBV) – a term coined by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) to understand and capture the full range of motivations, tactics and impacts of these behaviors, as well as provide a foundation for measuring it.

In the case of the Annapolis shooting, Ramos repeatedly threatened his former high school classmate over email and social media, which was so extreme that she chose to relocate. Despite being criminally charged for harassment in 2011, Ramos used his Twitter account regularly to attack the Capital Gazette journalists over an article covering the criminal proceedings against him, as well as the judge presiding over the case. This campaign of harassment eventually culminated in the deadly shooting in Annapolis in June.

Ramos is not alone. In 2014, Elliot Rodger uploaded several YouTube videos railing against women. These rants were fueled by his feelings of sexual rejection. Shortly afterward, he opened fire near the University of California, Santa Barbara campus. Rodger is considered to be part of the “incel movement,” an online community of men who are “involuntarily celibate” and blame women for denying them their perceived right to sexual intercourse. Alek Minassian, who killed ten people by driving a van down a busy street in Toronto, invoked an “incel rebellion” on a Facebook post released ten minutes before his attack.

These examples demonstrate a clear association between online misogyny and mass violence. Failing to detect and deter technology-facilitated GBV is a missed opportunity to prevent deadly consequences offline. Prevention must be founded in a full understanding of technology-facilitated GBV – what drives it, what forms it takes and what it looks like on different platforms. And everyone can play a role in bringing it to an end, including law enforcement officers, legislators, technology companies and researchers.

The impacts of technology-facilitated GBV can be profound, debilitating a survivor’s physical and mental health, safety, social status and economic opportunities. And as we have seen, these consequences frequently extend well beyond the individual targeted by the harasser, spreading death and suffering throughout the community. Unfortunately, the GBV that takes place online or over mobile technology is often not prosecuted nor even taken seriously. It is imperative that we research the connection between online and offline violent behavior and then act, collectively, both to protect possible victims and to identify perpetrators before their online crimes cross over into real-world tragedies.

About the Authors

Jennifer Mueller is a Program Associate at ICRW, where she collects and analyzes qualitative and quantitative data on gender-based violence and sexual and reproductive health and rights. Ms. Mueller holds a Master of Public Health degree in Epidemiology and Maternal and Child Health from the University of Washington School of Public Health.

Jennifer Mueller is a Program Associate at ICRW, where she collects and analyzes qualitative and quantitative data on gender-based violence and sexual and reproductive health and rights. Ms. Mueller holds a Master of Public Health degree in Epidemiology and Maternal and Child Health from the University of Washington School of Public Health.

Vaiddehi Bansal is currently pursuing her Master of Science in Public Health with the Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Ms. Bansal is completing her practicum with ICRW, where she analyzes qualitative data and prepares dissemination materials on sexual and reproductive health.

Vaiddehi Bansal is currently pursuing her Master of Science in Public Health with the Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Ms. Bansal is completing her practicum with ICRW, where she analyzes qualitative data and prepares dissemination materials on sexual and reproductive health.

Lila O’Brien-Milne is a Program Assistant at ICRW, where she coordinates research on gender-based violence and analyzes qualitative data. Ms. O’Brien-Milne graduated from Bryn Mawr College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Political Science, with a focus on Gender and Peacebuilding.

Lila O’Brien-Milne is a Program Assistant at ICRW, where she coordinates research on gender-based violence and analyzes qualitative data. Ms. O’Brien-Milne graduated from Bryn Mawr College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Political Science, with a focus on Gender and Peacebuilding.

Laura Hinson is a Social and Behavioral Scientist at ICRW, working to identify and reduce social barriers to sexual and reproductive health for men, women, adolescents and other marginalized populations. Dr. Hinson holds a PhD from the Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health at Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health, and a Master of Public Health from the Department of Health Behavior at University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Laura Hinson is a Social and Behavioral Scientist at ICRW, working to identify and reduce social barriers to sexual and reproductive health for men, women, adolescents and other marginalized populations. Dr. Hinson holds a PhD from the Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health at Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health, and a Master of Public Health from the Department of Health Behavior at University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health.